When the news about a possible ARAMCO sale hit about a year and a half ago, we posed a question: What if the Saudis have finally gotten the joke? The real return to holding oil in the ground has been negative over the last 44 years, as a succession of peak oil predictions were met by innovations in conservation and alternative energies that overwhelmed forces for higher prices. And those innovations look no less likely to do the same going forward.[1] What if the Saudis are looking to unload their oil reserves lest they face another 44 years of negative returns.

Recently, the Saudis have added a new wrinkle. Saudi authorities are simultaneously championing the hearty perennial story of coming oil shortages, while curtailing production. Tuesday brought the news that Saudi Arabia had agreed with Russia to extend production cuts into next year. This follows on the heels of a number of speeches made by key Saudi officials, warning that dangerously low levels of oil exploration put the world on a path to oil shortages and substantially higher prices, going forward.[2] The announced extension of oil production cuts was associated with a jump in both the price of oil and the S&P 500 Energy Sector index. This got us asking another question: Could the Saudis be trying to briefly boost oil prices to raise the valuation of reserves before the ARAMCO IPO? Or more bluntly, after 44 years of being the butt end of the falling-oil-price joke, are the Saudis holding auditions for a new chump?

Trained economists will reflexively scoff at this hypothesis. You don’t have to be a Chicago School ideologue to be skeptical about whether markets could really be myopic enough to fall for such a ploy. It’s a bit like arguing that umbrella factories sell for a higher price during rainstorms.

Nonetheless, students of the history of the long-running rising-oil-price gag might have quite a bit more sympathy for the story. What does resource economics 101 tell us about price levels and production strategies? We invoke Hotelling. Unless the real price of oil is expected to rise at the rate implied by the real yield on competing assets, holding onto oil in the ground is a bad investment strategy. As it turns out in practice, this unassailable notion seems to have quite a pull on conventional thinking. Specifically, since somebody is always owning the oil in the ground, conventional analysts seem quite wedded to the conclusion that the owners will, indeed, earn something like the return on competing assets. This, in turn, leads analysts to perpetually forecast that oil prices will be rising steadily from where ever they happen to be.

The problem is that the prediction of rising oil prices has been consistently wrong for nearly half a century. In the early 1970s,the real price of oil jumped roughly to today’s level. At that point, many breathless forecasters dutifully predicted rapidly rising prices over the medium and longer run. Peak production levels were destined to collide with rising demand from rapidly growing emerging economies, and chronic shortages coupled with skyrocketing prices were in our future. Of course, somewhat cooler heads predicted at the time, [3] that a rising real price of oil would be sufficient to elicit strong supply and demand responses, preventing a crisis. They nonetheless stuck with the conventional wisdom that oil in the ground would offer a competitive real return. In reality? The supply and demand responses dwarfed conventional expectations and, with plenty of oil on hand, by 2000 the real price of oil had fallen back to its 1973 level.

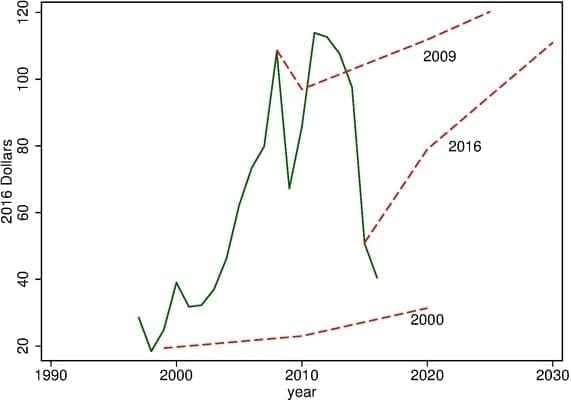

Beginning in 2000, the markets fell for the same joke again. This time we can use the IEA’s long-run oil price forecasts to illustrate the argument (Fig. 1). For those familiar with the numbers, note that the prices in the following paragraph are annual averages and in 2016 dollars.

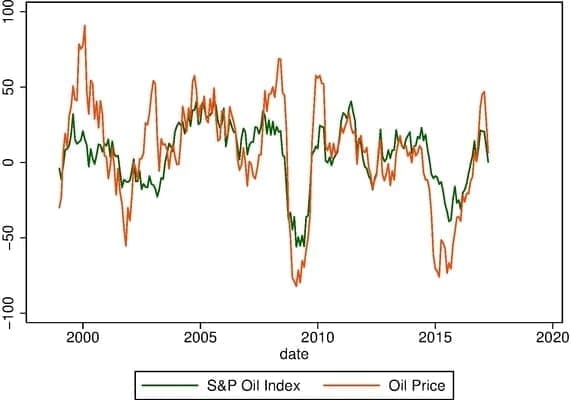

Based on the spot oil price of $25/bbl in 1999, the IEA in 2000 forecast a real oil price growing at a respectable 2.3% rate through 2020, ending at around $40/bbl. Shortly after this forecast, short-run factors associated with growth in demand from emerging economies such as China began pushing up the price of oil, which reached $100/bbl in 2008. The IEA’s oil price forecast in 2009 showed a brief decline due to the financial crisis, but after bottoming out, the real price of oil was predicted to grow at a 1.4% rate through 2020. Instead, supply and demand innovations again pushed the oil price back to the $50/bbl range. In the latest IEA forecast, the real price of oil is again growing steadily, this time from the new lower base. Whatever the current price of oil, it seems, the price is headed up. Some evidence that this fallacy is reflected not only in expert forecasts but in market valuations can be seen in the close association between the price of oil and the S&P Energy Sector index (Fig. 2). Let’s speculate that the Saudis might have noticed this linkage and return to the Saudi actions of late. While talking up the coming shortage and arranging production cuts, the Saudis have claimed that they are simply building a bridge to the inevitable much higher future prices. A bridge, or a pier?

We are not claiming to know more about the price of oil over coming decades than anybody else. But any of us can review the past several decades and read daily about the remarkable pace of technological advance in the energy field. That’s enough to engender deep skepticism about the prospects for consistently rising real oil prices. If the Saudis, awash in hundreds of billions of barrels in reserves, share that skepticism, could we blame them for trolling for chumps? And it might work. You probably won’t get a better price for your umbrella factory on a rainy day, but Saudi success simply requires that oil markets, for a few more months, fall for a gag that markets been duped by for nearly half a century.

Notes:

1. Remarkable breakthroughs are announced almost daily. Take a look at a roof shingled with Elon Musk’s new solar shingles technology. The roof looks like your old roof. It lights up your house. It powers your car. And over its useful life in most areas of the USA, the roof pays for itself and then some. Even adjusting for the usual Musk hype, we can imagine the efficiency of this kind of technology in ten or twenty years. [back]

Resources for the Future, Energy, the Next Twenty Years, 1979 [back]