By: Keely Kriho, Chloe Center Graduate Fellow

“When people blame migrants for ‘crossing illegally,’ it ignores the history of a border that’s been managed unevenly and unfairly to the point where migrants are being excluded…Standing there at the border felt like encountering a line between who’s considered human and who isn’t. But migrants still continue to fight for themselves. Manuel, by being there with us and telling his story, was risking his safety and status. But for him speaking out was more important and that really stuck with me.” — Halima

Over Fall Break 2025, ten Hopkins undergraduates enrolled in the course “Introduction to Critical Diaspora Studies” travelled to Tucson, Arizona, to participate in an experiential education opportunity. It was hosted by BorderLinks, a community-based organization in Tucson that designs interactive educational experiences to help students critically examine the violent and complex history of the U.S.-Mexico border.

All photos by Keely Kriho unless otherwise noted.

Sponsored by the Chloe Center for the Critical Study of Racism, Immigration, and Colonialism, and organized by director Stuart Schrader, with the assistance of Chloe Center graduate fellow Keely Kriho, the delegation met with representatives from organizations working for migrant justice in the borderlands, as well as individuals who shared their migration stories and the work inspired by them. This report includes quotations from undergraduates in the course, recorded in daily reflection essays and other report-backs.

Hopkins students left the experience not only having witnessed the violence and complexity of the U.S.-Mexico border, but also with tools to translate what they learned into concrete action back in Baltimore and their communities. The alignment between the Critical Diaspora Studies major and BorderLinks allowed Hopkins students to connect classroom readings and conversations to their experiences in the borderlands, highlighting a core tenet of CDS: critically studying the intersections of racism, colonialism, migration, and advocacy across contexts, geographies, and movements.

“Being [in Nogales], seeing the wall, and listening to Manuel [BorderLinks staff member] talk about his community made everything feel so much more real than anything I’ve read in class. These are people’s lives, families, and memories that live in these border towns.” — Michelle

BorderLinks programming is structured around three main questions:

- Why do people migrate?

- What happens during the migrant journey?

- How do policies impact people?

The morning after arriving in Tucson at the BorderLinks headquarters, our delegation leader, Brinley Carillo, asked students to brainstorm questions they had about migration and the U.S.-Mexico border. The students’ inquiries ranged from the role of U.S. policy and global interventions in causing migration to the position of Indigenous peoples in border politics to solidarity against settler-colonialism and border violence in different parts of the world. By the end of the trip, Brinley told the students, all of their big and small questions should be asked and answered.

“Many people say ‘why can’t all immigrants enter legally?’ or ‘they need to do it the right way’ but this is a nearly impossible way to enter the country. Many people are running away from situations that are impacting them presently and need an immediate solution but the system doesn’t allow for this which is why many people enter the country undocumented to try and make a better life for themselves and their families.” — Yesly

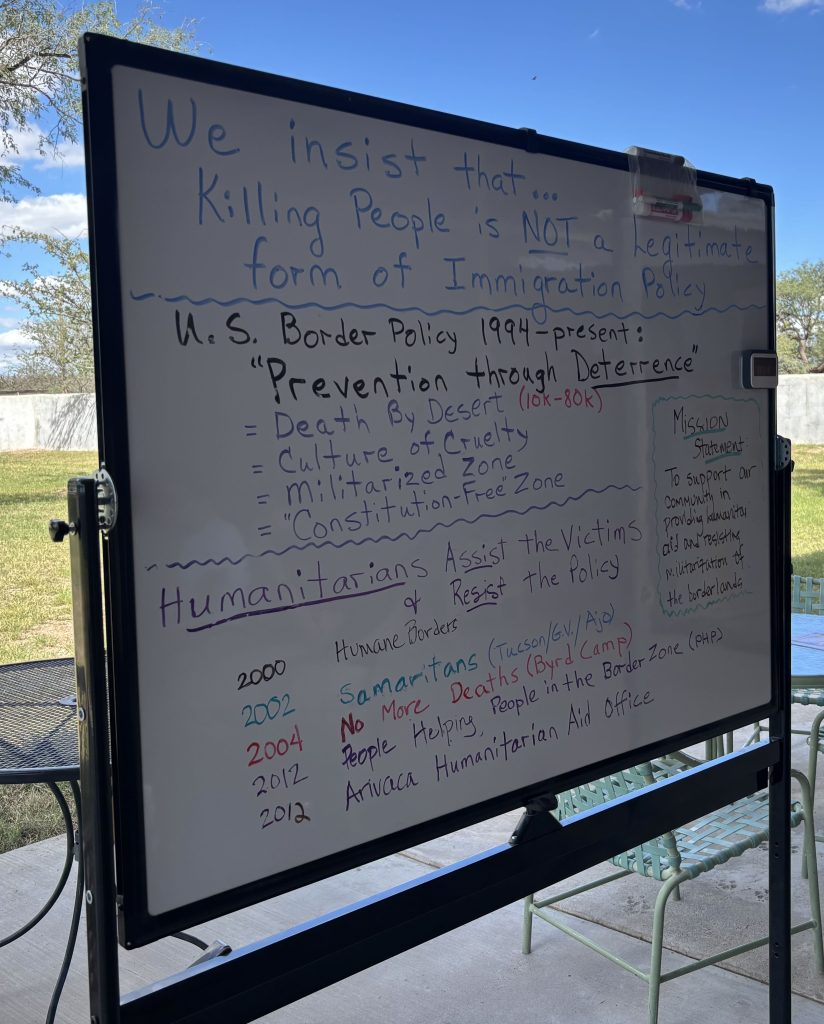

On the first day in Arizona, the Hopkins delegation loaded into a van and drove to Arivaca, a small town an hour south of Tucson and 11 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, to participate in a water drop with the humanitarian aid organization No More Deaths (No Más Muertes). No More Deaths aims to end death and suffering in the Sonoran Desert by dropping water, food, clothing, and other supplies near paths frequented by migrants. The NMD volunteer leading our water drop, Kevin, explained that since the implementation of the policy of Prevention through Deterrence in 1994, migrants have increasingly been forced to enter the U.S. through the desert, significantly increasing migrant deaths due to the dangerous climate, terrain, and inhospitable conditions.

The Hopkins delegation joined NMD on a water drop near Arivaca, hiking for a mile into the desert with 8 gallons of water and packets of non-perishable food. The students noted how challenging the hike had been, given the heat, the terrain, and the unfamiliarity of the desert environment. They discussed how much more difficult and stressful it would be to travel through the desert at night in much colder or hotter temperatures, without maps, food, water, or adequate clothing, shoes, or shelter, and in constant fear of border patrol and vigilante militias.

“[The desert walk] was really difficult and the terrain was pretty unstable. Although it was very challenging for me, the whole experience opened my eyes to the journey migrants take that I’ve only heard about but never experienced first-hand.” — Elham

“It was hot, hard to avoid getting pricked by thorns…it really showed me how much these people go through, and how they are choosing between violence and death and violence and death with a migrants choice of a better life in the US…One thing I learned was how migrants are escaping in search of not just a better life but life in general.” — Ari

“Being physically present in the same environment that thousands of migrants risk their lives crossing made everything I’ve learned about migration feel a lot more real. Experiencing this made me realize how unimaginable it must be for someone traveling this landscape for the first time, without guarantee of meals, medical help, or even water.” — Michelle

In addition to No More Deaths, our delegation visited the headquarters of People Helping People in the Border Zone, a community organization in Arivaca that provides humanitarian aid resources to local groups—specifically backpacks filled with food and supplies—and hosts educational trainings that advocate for the demilitarization of the borderlands. Since 1981, PHP has shared that there have been over 4,200 migrant deaths recorded in the desert nearby, a number far smaller than the real death toll. Humanitarian aid groups like PHP have been targeted by Border Patrol, law enforcement, and armed militias, yet these groups continue to provide humanitarian aid to migrants with the belief that—as is seen on posters around southern Arizona—“Humanitarian aid is never a crime.” Each organization also subscribes to the framework that their work, as Michelle remembers in her reflections, “is an act of solidarity, not saviorism.”

Even with this push back [from vigilante groups and border patrol], PHP continues to help, and they organize protests, document Border Patrol abuses, and offer direct aid. They just refuse to accept death or militarization as normal on the border—and it’s powerful.” — Katie

The next day, Hopkins students traveled to the border wall in Nogales, a city with a port of entry where people can cross between Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. Most students had never seen the border wall in person; the wall in Nogales, recently reconstructed via Operation Safeguard, is made of thick steel beams multiple stories tall. Manuel—a current resident of Nogales, Sonora, and BorderLinks staff member—provided historical and political context about the border wall. Manuel sought to challenge students’ assumptions about the normalization of the border wall and the inherent danger in border zones.

Manuel shared his own migration story: he had left his family in Michoacan after the neoliberal economic policy of the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) made it impossible to find work there. His family lives on both sides of the border, and he crosses frequently, meeting with BorderLinks delegations and conducting humanitarian work in Mexico. One student, Eli, wrote that a key takeaway from Manuel’s talk was that “borders are entangled with culture, capitalism, and community.”

Manuel shared the story of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16-year-old Mexican boy who, after allegedly throwing rocks at the border wall from the Nogales, Sonora side, was shot over ten times from the U.S. side of the border by Border Patrol officer Lonnie Swartz. After years of attempts to publicize this incident and go to trial, Swartz was indicted but eventually acquitted of all charges and walked free. The impunity of Border Patrol and the injustice of the legal system led Manuel to ask a question that problematizes stereotypes of the U.S.-Mexico border: “Where is the violence coming from?”

Manuel challenged the students to recognize that the militarization of the border, neoliberal economic policy, and the impunity of Border Patrol result not from any natural existence of borders but from violent U.S. policies and actions that create the border itself. Manuel contested sensationalizing narratives that the communities around the border are prone to violence or danger. The real threat, he emphasizes, is the militarization of the border, not the people who live on either side. Manuel asked the students to imagine what it would be like to be in Nogales if there were no border wall there. He called on the students to share their experience at the border wall with their communities back home.

Dr. Schrader reflected on the landscape while at the border wall, noting that it was a social, political, and historical creation. Pigeons were flying back and forth over the fence while the group stood in the sun and conversed with Manuel. “To these birds, introduced by European settlers, the wall was no impediment, and it was also not a natural or inevitable feature of the Sonoran landscape,” he noted. “The pigeons have been flying across this line on the map long before it actually existed, and they will continue to do so when the fence, if not the line itself, ceases to exist.”

“[The death of José Antonio] showed how militarization didn’t make the border any safer and only made it easier for violence to be inflicted on others (migrants)” — Halima

“One thing I’m excited to share is the feeling I had when listening to Manuel’s story. I also think when he asked the group how we felt during the talk standing right smack at the border is something I’ll carry with me to Hopkins, back home to my family in both the US and even Mexico. It is not to say I forgot we were at the border in that moment during that talk but my body and mind did not feel uncomfortable or tense.” — Katie

“[The border] it isn’t scary like people constantly say it is. There are a lot of misconceptions when it comes to the border, which are not true.” — Yesly

Throughout the students’ time in Arizona, BorderLinks delegation leader Brinley created opportunities to connect the struggles of migration at the U.S.-Mexico border with the challenges faced by Indigenous peoples in the borderlands. Students learned about the work of Sebastián Quinac, a Kaqchikel Maya activist from Guatemala, who provides translation and assistance to Indigenous migrants who do not speak Spanish or English. Quinac’s presentation emphasized that the difficulties faced by Indigenous migrants are incredibly complex and often ignored, leading to additional instances of injustice and violence.

Nellie Jo David—a lawyer specializing in Indigenous people’s law and policy, a citizen of the Tohono O’odham Nation, and a co-founder of the O’odham Anti-Border Collective—shared about her work opposing the construction of the border wall in the Tohono O’odham Nation. The recent construction of the border wall, the fact that O’odham lands sit directly in the Prevention through Deterrence corridor, and the complexities of tribal, state, and federal law, make the politics of migration contested and challenging for the Tohono O’odham Nation. Nellie Jo emphasized that O’odham people have always been opposed to the border, which is a colonial construction that has separated the O’odham people since its imposition in the mid-19th century.

The students were fortunate that the delegation coincided with an annual folk arts festival, Tucson Meet Yourself. At the festival, they danced to the “waila” sounds of the legendary O’odham band Gertie and the T.O. Boyz.

“One theme that has stood out to me is the intersection of indigeneity and migration. The No More Deaths volunteer mentioned how pre-Trump, indigenous border crossers would just be returned to Mexico without the 30–120 day detention due to lack of translators to allow courts to fairly hear cases. Sebastian later in the day also gave more insight into the indigenous perspectives especially regarding the loss of identity and culture. The indigenous narrative of migration to the US is one often excluded from mainstream migration media, and it made me think about why, and what effort look like to counter dominant narratives.” — Eli

“[Nellie’s] talk really put into perspective how advocacy work can affect you, especially when you’re in it for personal reasons…Even her going to law school to prevent the wall from cutting into her territory just for her to not stop it…I really felt for her and applaud her.” — Halima

Muna Hijazi, a Palestinian-American resident of Tucson and a member of the Arizona Palestine Solidarity Alliance, provided context around the connection between migrant justice in the borderlands and justice for Palestine. Muna taught the delegation to make warak enab, a traditional Palestinian dish of rolled grape leaves filled with hashweh, a rice mixture. While preparing the warak enab, Muna shared about her work with Alliance, which seeks to build a coalition opposing the occupation of Palestinian lands, the genocide in Gaza, U.S.-Israeli partnerships, and the increased militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Muna described the deep connections between U.S. and Israeli histories of settler colonialism and the displacement of Indigenous peoples in both geographies, as well as the militarization of both regions against immigrants and Indigenous peoples. This includes the same technology being used in both locations, including Elbit surveillance towers, which the group saw firsthand just outside Arivaca. Muna’s talk provided students with crucial information about connections and solidarities between Arizona and Palestine, emphasizing the necessity of global solidarity against colonialism, racism, and military-industrial development and investment.

“I knew the border was heavily militarized (with Israeli technology) but didn’t realize the extension of the MIC to Arizona through Raytheon, Caterpillar, academic collaborations, etc.…The story of José Antonio also mirrored the same tactics, power dynamics, excuses, and lack of accountability that exist when IDF soldiers kill, detain, or torture Palestinian children.” — Eli

Throughout their time with BorderLinks, members of the Tucson community shared their own migration stories with the Hopkins delegation. Dora Rodríguez told her story of fleeing El Salvador during the civil war in 1980. She barely survived a harrowing journey that took the lives of 13 of her companions in the Ajo Valley. Her recently published book, Dora: A Daughter of Unforgiving Terrain, chronicles her story of migration, recovery, and community-building and advocacy for migrants in Arizona. Dora’s experience helped catalyze the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s, which gave rise to present-day humanitarian aid and migrant justice organizations in the borderlands.

Dora founded the organization Salvavision, which provides support to migrants seeking asylum or who have been deported by connecting them with housing, financial assistance, legal aid, and helping with community integration. Dora asked students to reflect on their own families’ migration stories, from Ethiopia, Nigeria, China, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sweden, Poland, Lithuania, Mexico, El Salvador, and many other locations throughout the world. She emphasized that all students, unless they are Indigenous to what is now the U.S., have a migration story; and that migration is an experience through which solidarity, care, and community can be built.

Wendy, a staff member at BorderLinks, shared her migration story from El Salvador to the U.S. after she led Hopkins students in a pupusa-making workshop. Wendy’s story has been filled with struggles, setbacks, and financial difficulties for herself and her family, but it is also one of perseverance and community. After she first came to the U.S., Wendy was deported to Nogales, Sonora, to await an asylum hearing. While she was there, she lived in a communal house with other women awaiting their hearings, and she learned to embroider “mantas,” pieces of cloth with intricate designs. Wendy began creating mantas to sell in order to support herself and her family. Now, she lives with her family in the U.S., but continues to teach embroidery to women in Nogales, Sonora, so that they can support themselves like she did. Wendy encouraged students to make connections among the many injustices of the U.S. border regime and support migrants who are forced to navigate the complexities of immigration.

“I am excited to share Wendy’s story about selling Mantas to support women back in El Salvador. I think she is a great of example of how migrants are not victims but often leaders in their home communities and in the United States. Wendy exemplifies the agency migrants have even in the face of state repression, and I look forward to sharing her story with others at Hopkins.” — Chris

“The most impactful experience today was hearing Wendy’s story of the barriers she faced getting to where she is today,” particularly “how the government made I so difficult for her to proceed with the process of becoming a citizen legally given the violence she fled from in El Salvador. I loved her story about embroidery and the collective of women that she helps support because it is incredible how smart and innovative these women have become to support their families.” — Camila

Thanks to BorderLinks, Hopkins students witnessed, experienced, listened to, and discussed the history, politics, and effects of the U.S.-Mexico border, as well as the struggles of migrants in the borderlands. Throughout the weekend, they brainstormed individually and collectively about how they would bring what they learned back to Baltimore. From sharing stories from Arizona with family and friends, to connecting with local community organizations, to developing panels or workshops to share information with other Hopkins students, to getting involved in organizing around migrant justice, students left with concrete ways to use what they had learned and experienced to the Hopkins campus, the CDS major, the Chloe Center, and beyond.

“One thing I am excited to share back in Baltimore and with my family are the stories of all the people we met this week, from Wendy, Manuel, Dora, José Antonio Rodriguez, Sebastián. When I called my mom one of these mornings, I told her Wendy’s story and we both ended up crying because of the struggles of domestic violence against women, struggles of obtaining citizenship or feeling safe surround us and to hear her story and how she overcame all these barriers and gives back to her community in El Salvador is deeply moving.” — Camila

“This experience made me realize that witnessing injustice comes with responsibility. It’s not enough just to feel the emotion from what I saw and heard, there has to be action that follows.” — Michelle

The Chloe Center is grateful to Cailan and Brinley and all of the BorderLinks staff for their support, as well to Christopher Amanat (KSAS ‘28) for making the connecting between the Center and BorderLinks and to Joshua Hunt for all of his work behind the scenes to make the delegation possible. Stuart Schrader would particularly like to thank the students and Keely Kriho for their seriousness, patience, hard work, and generosity.