We may have reached a point where there are simply not enough people who want to work to fill all the available jobs in the United States.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today that in March there were 6,550,000 unfilled jobs in the country, on a seasonally adjusted basis. It reported there were 6,585,000 unemployed people that same month. That computes to 1.005 unemployed person for each available job.

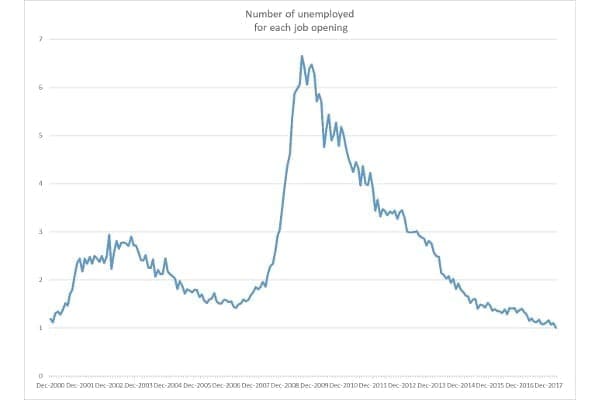

In the summer of 2009, at the height of the Great Recession, there were 6.84 unemployed workers for each job opening.

The current ratio of 1 to 1 is the lowest ever reported, although it should be noted the figures are not available before 2000. It seems likely that the job market was even tighter in 1999 than it is now.

The job openings figures are reported a month after other job figures, which is one reason they get little attention. Last week the Labor Department put the number of unemployed people in April at 6,346,000. It seems likely that there were more jobs than available workers in that month.

In 1999, as now, there were newspaper articles on the lengths some employers were going to in their effort to fill positions, including hiring ex-convicts. But so far wages do not seem to have risen very much in this cycle, a fact that has perplexed some analysts.

There are plenty of caveats to the numbers. The unemployed figure is an estimate of how many people without work were looking for it during the month, and is based on the Household Survey taken each month by the Census Bureau. It only counts as unemployed those who say they looked for a job unsuccessfully—not those who say they would like to work but are too discouraged to look.

The job openings number comes from a different survey, one of employers. Both sets of figures are seasonally adjusted.

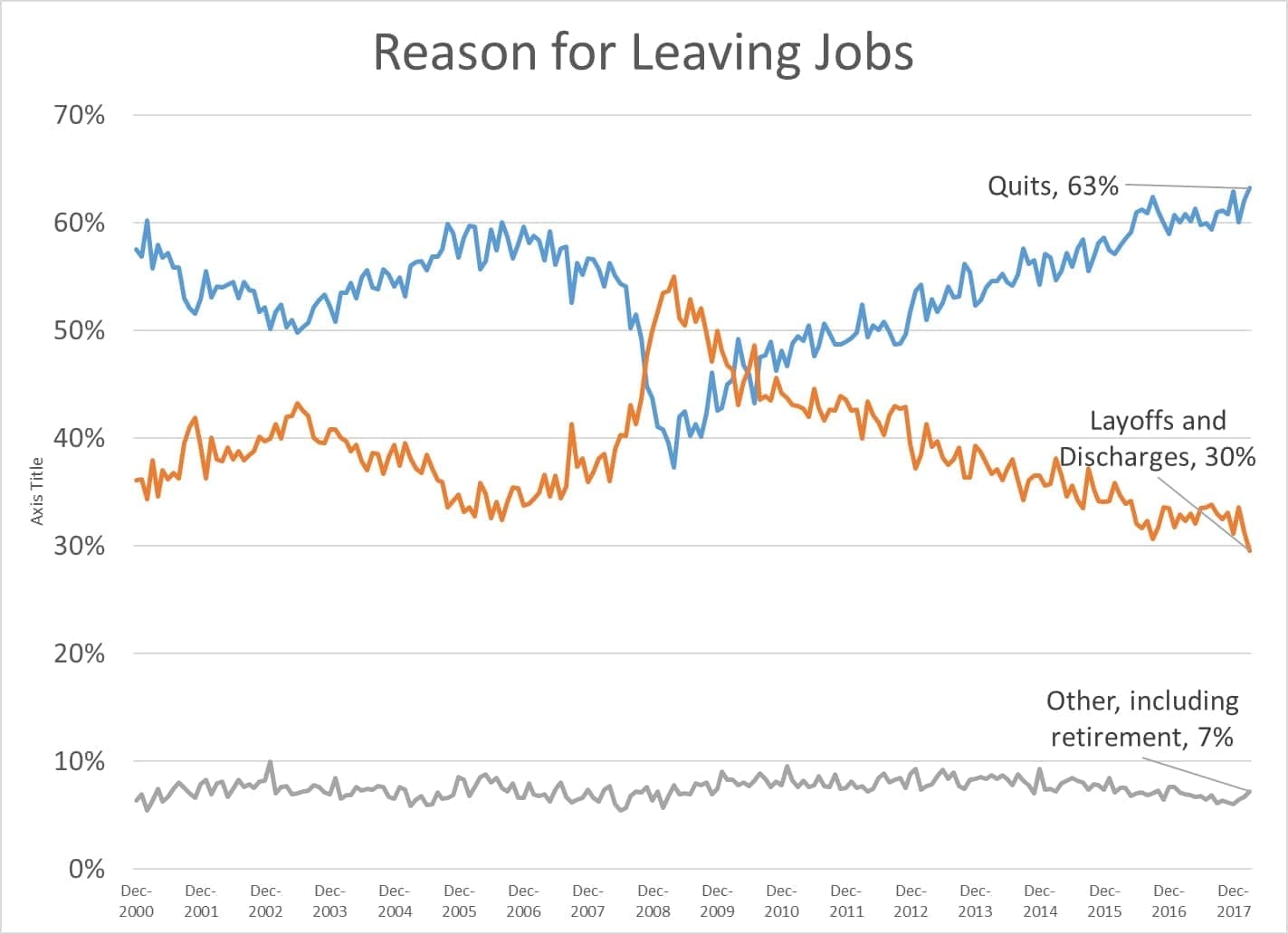

That survey also asks employers about how many people were hired during the month, and how many left—and the reasons for the departures. In March, the survey found that 63 percent of the departures were due to workers quitting—many presumably because they had found a better job—and 30 percent left because they were laid off or discharged. That is the highest proportion of quits ever recorded, and the lowest proportion of firings. The remaining 7 percent left for other reasons, including retirement and transfers to other offices of the same employer.

The tightness of the labor market makes it seem like an unlikely time to be employing massive fiscal stimulus—through increased federal spending and tax cuts—and an equally unlikely time to reduce the number of legal immigrants allowed. But that is what is happening in Washington.