The global COVID-19 outbreak now sports exponential growth rates for cases and deaths on every continent save Antarctica. Students of the economy must add that we are also in the midst of an unprecedented blow to global output, income, and employment. In financial markets, the pace of decline for equity and corporate bond prices exceeds any on record.

What we confront is a public health crisis that has elicited necessarily radical action, in the form of extreme social distancing. Perversely, for at least the next several months, the better we do at shutting down human-to-human contact, the more dramatic will be the slide for sales, employment and company cash flows. Absent enormous proactive policy actions, a Main Street/Wall Street deadly dance will put the U.S. and the global economy into deep contraction, irrespective of the resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sensibly, the Federal Reserve, the Congress, and the White House in concert are delivering essential relief. The near-term swoon is inescapable; enacted policies hold out the hope that the plunging activity will not feed on itself.

Do the economic costs of ongoing social distancing outweigh the benefits of fewer deaths? They do not.

Several months from now, the economy/epidemiology tradeoffs will be the issue of the day. In current circumstances, in contrast, there is no tradeoff. Deaths from COVID-19, over the past week, have risen at a 32% per day rate. If deaths climb at only half that trajectory into early May, the total number of American deaths would approach 300,000.

Independent of government dictate, widespread panic – directly a function of the reality of soaring deaths – would impose a bottom up shutdown of economic activity. Thus, at least for the next several months, the economic and epidemiological calculus comes to the same conclusion. We need to impose radical social distancing, to stem the surge of COVID-19 infection.

NOT A FORECAST, A NOWCAST

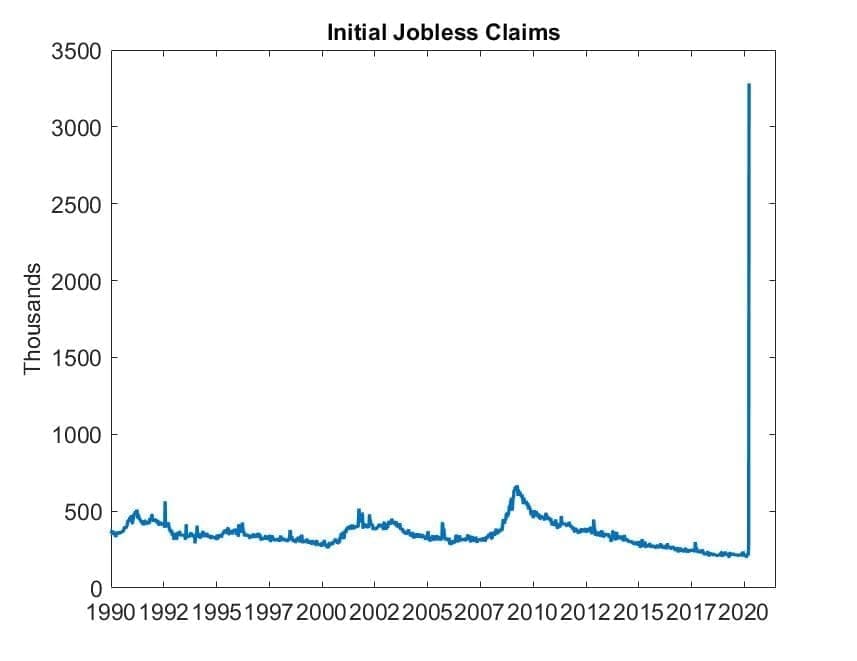

To repeat, the collapse for economic activity, a direct result of social distancing, is not a prediction. It is already well underway. When workers lose their jobs, they file for unemployment benefits. In deep recessions, weekly filings climb to peaks around 700,000. Last week, as the improbable chart below depicts, weekly filings eclipsed 3 million. Nothing even remotely close to that has been recorded since data collection began in 1967. An explosive rise for joblessness is baked into the cake, given the collapse for activity in the transportation, accommodation and food services industries. Those sectors alone account for 6 percent of GDP and 12 percent of employment. Simply extend this level of filings for a few more weeks and the U.S. unemployment rate will go from 3.5% – the lowest recorded rate in 50 years – to a rate in the teens, something not seen since the 1930s Great Depression. Nothing can rescue current economic activity, which is contracting at a double-digit annualized rate. The $2 trillion stimulus package, which was passed by the U.S. Senate earlier this week and is headed back to the House for a final vote, is meant to stem this tsunami.

CORPORATIONS AND CRISES

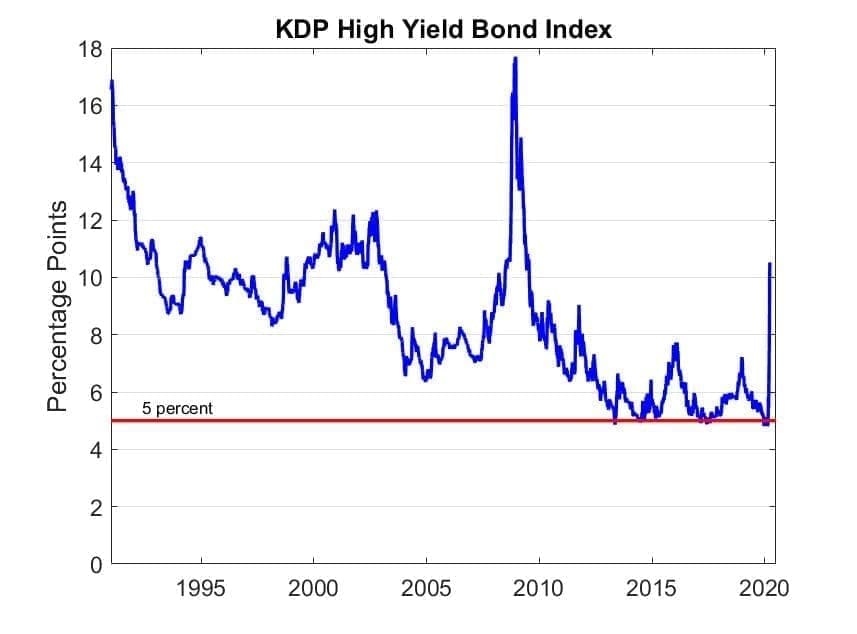

We spoke, above, of likely damaged economic machinery thwarting economic recovery. That machinery is largely found on Wall Street. Companies collect dollars, spend dollars, service debt, and keep the rest. The ability to service debt is what keeps companies out of bankruptcy. Over the past several years, many risky companies issued large amounts of debt, in part in reaction to super low borrowing rates. As the chart below makes clear, junk credits – highly risky companies – had access to loans at rates below 5%, an unheard of lending rate for these riskiest of firms.

Writing checks to companies to stem bankruptcies sounds an awful lot like the response to the financial crisis of 2008-2009. The bailout on this occasion will be more to Main Street than to Wall Street, and because the Pandemic crisis was not caused by mistakes by U.S. firms, concerns about moral hazard should be second order. The Senate has agreed on a $2 trillion package that will cushion the blow. It does not, and cannot, avoid a sharp contraction in economic activity in the second quarter. If goods and services are not being produced, they do not show up in GDP. But it will make the contraction smaller than it would otherwise have been. More importantly, it keeps the firms going, which makes it possible to have an economic recovery when the shock eventually passes. It is expensive, and is only part of how the deficit will explode, with reduced tax revenue and automatic stabilizers being another large part. But there is the fiscal space to do this, and it gets us through the near-term effects of the virus without economic catastrophe.

AND BEYOND THE NEXT FEW MONTHS?

We are all praying for a material payoff, in terms of flattening the pandemic curve, over the months immediately ahead, and the widespread consensus among epidemiologists is that we need at least a couple of months of social distancing to stem the pandemic. If economic policies are aggressive and put in place quickly, the economic costs can be managed.

But beyond the very near term, the lockdowns will have to be eased at least to some extent. Farms, for example, need to keep producing, and that will mean workers are needed. We can get along for quite a while without new cars, houses or even clothing. Food is something else.

All of this suggests to us that around summer, a second calculation will have to be made. A multi-month lockdown – whether driven by federal authorities or state and local leaders – wild central bank cash infusions and enormous federal fiscal stimulus can hopefully flatten the COVID-19 curve while also averting economic disaster. It is, however, nearly impossible to sketch out a strategy to keep the economy afloat, amid the possibility of a lockdown in place into the fall or 2021, when it is hoped a vaccine will become available.

A yearlong lockdown would guarantee major supply disruptions. Bankruptcies will dominate, the jobless rate will exceed Great Depression levels, and there is nothing that monetary or fiscal stimulus can do to avert this scenario. In such circumstances, deaths from the indirect effects of the economic catastrophe would soar, not to mention the other human costs of mass unemployment.

The U.S. was not well prepared going into this pandemic. However, appropriately aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus can buy some time to get more ventilators, more test kits, and more intensive care capacity. It also allows epidemiologists to get more data on the spread of the virus and its mortality rate. With enough test kits, randomized testing of the general population might give us very important information. That information may help us do some grim math. To get the economy moving again will require people to, well, move again. There will be health costs to doing that, and difficult tradeoffs to face. The decisions will not be easy ones.